The UK's Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is now a well-oiled, privacy-averse 'surveillance machine', a new report from UK charity Privacy International has claimed.

The investigation found that suspected benefit fraudsters are being subject to surprisingly intrusive and immoderate surveillance techniques.

What is the DWP?

The Department for Work and Pensions is the arm of the UK government responsible for child maintenance, pensions, and maintaining a welfare and benefits system that supports those who have fallen on hard times.

Currently headed up by Suffolk Coastal MP Therese Coffey, it is the largest of the UK's government departments when it comes to both staff and expenditure, the latter of which has accounted for almost a third of all government spending in recent years.

The department has faced its fair share of scandals in the past and has been widely criticized for both the design and implementation of Universal Credit, the government's centralized, singular welfare payment.

The DWP is at times dragged in but often contributes (surprisingly heavily) to the vicious, unempathetic age-old public discourse surrounding benefit fraud, despite such crimes only accounting for less than 1% of the department's overall expenditure. Last year, quite embarrassingly, it was revealed they lost more employee disability discrimination cases than any other UK employer between 2016 and 2019.

Shedding light on surveillance

It seems the will to catch these benefit fraudsters has led the DWP down a dark and overly intrusive path when it comes to citizens' privacy.

It was revealed last weekend by charity group Privacy International that the DWP is using immoderate surveillance strategies during investigations after they combed through the department's 995-page staff guide published in 2019.

The report also found that hundreds of private organizations – including universities, bing clubs, airlines, and even the BBC can be asked to hand over data on suspects in active fraud cases. PayPal is held up in the guide as an example of a company happy "to provide information in response to a standard Data Protection Act letter", and credit reference agencies, banks' telecommunication services are identified as intelligence sources.

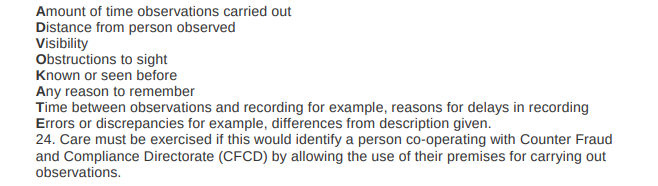

The document also gave guidance to employees on how to snoop through a suspect's social media and other 'open-source intelligence' sources, as well as how to obtain CCTV footage. The guidebook also aims to teach employees the dos and don'ts of recording details of physical surveillance missions with a handy acronym:

Privacy International notes that there is, in this guide, a section on what this sort of footage and evidence can help to establish, but it has been redacted from the copy available to the public.

Is the DWP doing its job?

What the law says

The DWP is regulated by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA), which was first signed into law in 2000. This allows specific public bodies – such as the Department for Work and Pensions – to carry out surveillance on UK citizens.

However, the Department is only authorized to conduct 'directed surveillance', which is considered 'covert' rather than 'intrusive' and conducted for a specific purpose. The DWP couldn't by law, for example, wiretap phones to obtain communications data.

The law also states that the DWP can't obtain information from a CHIS (Covert Human Intelligence Source) under the RIPA, as the Department's 995-page guide suggests. Privacy International was left puzzled by the eight pages in the guide regarding how to obtain and use information from CHIS, concluding that there seems to be 'no hard limit on the granularity of information' the DWP can obtain from CHIS.

A question of priority

Importantly, Privacy International is not directly challenging their right to investigate suspects in any sense, but rather, arguing that the surveillance methods being used are excessive and part of a misplaced emphasis on fraud cases over Universal Credit delivery:

We believe a good welfare system is a system that delivers benefits to all those who need them, with delivery at the core of its mission rather than fighting alleged fraud cases.

However, in a statement seen by the Guardian, a spokesperson for the government department said that report "grossly mischaracterizes" the department's powers, which it notes are subject to independent scrutiny:

The limited powers that the department does possess are used to prevent and detect potential crime, with surveillance conducted only when the department is investigating potential fraud, and even then only in cases where all other relevant lines of inquiry have been exhausted.

The response is unlikely to change Privacy International's conclusions. The group believes the department had undergone an ugly transformation into a 'surveillance machine', where "people are employed to spy on others, where deals are struck with companies and the media to track down individuals and expose their lives in the papers."

Automated welfare: algorithmic assistance

The second part of Privacy International's report, amongst other things, vaguely details how an algorithm is used to identify potential benefit fraud suspects. The lack of transparency, the organization says, is alarming:

We have a government body refusing to tell us how the algorithms they use flag individuals for investigative work because they fear revealing it will facilitate fraud. On the other hand, we have that same government body over-promoting their cutting-edge artificial intelligence in their annual report, only to find that, when pressed on it, the DWP can only admit to the system being in its early development stage at most.

Once again, Privacy International is not criticizing the use of algorithms outright in these situations but is instead pointing out that there seems to be little oversight and that 'human intervention' will always be needed on final decisions, especially considering the live's of those rightfully due their benefits depend on the DWP.

Despite FOI requests revealing some data, Privacy International still has not been able to ascertain the categories of data that are being used to identify suspected fraudsters or the criteria for detecting fraud, fueling privacy concerns further.

Encouraging the media circus

Another interesting part of the guidebook is information on how to portray the Department's work positively for media purposes. The guidebook states that media coverage of the cases helps to spread the word that the department is prepared to crack down on benefit fraud.

In part 2 of the report, there is a 10-page section entitled 'Publicising investigation outcomes' which includes details of some information on their PR procedures, but Privacy International notes that there seems to be a separate document of the same name that is not publically available.

This is likely how the DWP has operated for years, but closer scrutiny, provoked by work like Privacy International's, could lead to both practices and department culture improving.