COVID-19 Malicious Domain Report: Mapping malicious activity throughout the pandemic

For as long as human civilization has flourished, we have had to deal with the realities of infectious disease. Between 541 AD and 750 AD, The Plague of Justinian decimated an estimated 50 million people, roughly half the world’s population. Some 800 years later, the same bacterium resurfaced in the form of The Black Death, claiming 200 million lives in just four years.

While pandemics are nothing new, the novel Coronavirus is the first truly global pandemic to ever take place against a digital backdrop and the implications are proving profound. Never before in peacetime have we witnessed such curtailment to civil liberties at such scale. And yet, the Internet has somehow made these restrictions to our way of life more palatable. We’re still connected to loved ones and family; many organizations, although by no means all, have been able to adopt work-from-home models thanks to high-speed connectivity and the plethora of off-the-shelf cloud-based solutions available. As if the World Wide Web was not already deeply engrained in the fabric of our society, it has taken on new meaning, now a vital means of information, communication and comfort.

Unfortunately, this absolute reliance on digital connectivity, combined with a heightened sense fear and anxiety has created the perfect storm for cyber-criminals.

When it comes to digital impact of the pandemic, an extraordinary amount of research has already been made publicly available. Almost every threat intelligence organization has done their best to open their data up to the intelligence community. The Covid-19 Cyber Threat Coalition has done a remarkable job at bringing these various commercial forces together. Microsoft also recently announced that it had open-sourced its COVID-19 related threat intelligence.

However, many of the datasets available draw almost exclusively on proprietary systems. They are a singular source of information. Our research methodology differs in that we are drawing on aggregated data from across some of the best-known security vendors in the industry in order to inform analyses. We have stored and shared all data regardless of whether a domain is taken offline or not. In essence, we have created a time capsule, rather than a real-time snapshot. This pandemic is likely to prove a pivotal point in our relationship with technology and will undoubtedly be studied by academics, social scientists and cybersecurity researchers for generations to come. Our hope is that our approach provides a vendor-neutral and comprehensive overview for researchers to draw on in the future.

As well as making all of the data publicly available throughout the process, we have created a simple interface so that members of the public can query our dataset in order to understand if a domain has been flagged as malicious.

Methodology

This project started out with one simple objective - to gather as many domains related to the pandemic as possible, identify whether or not they were being used for malicious purposes and share that data with the public. Thanks to both VirusTotal and WhoisXML API, we were able to take expand the scope of the research well beyond our initial ambitions.

WhoisXML API

WhoisXML API owns perhaps the largest private WHOIS database for gTLDs and ccTLDs available on the web today. Its customer base includes fortune 500 companies, threat intelligence organizations, security vendors, cybercrime units and government agencies.

During the first phase of research (late March), we used Certificate Transparency Logs and open datasets to inform our data collection. Our partnership with WhoisXML API provided us with a robust method to actively monitoring domain registrations on a daily basis.

We have also used both their historical records and APIs to ensure our dataset is as complete and accurate as possible.

VirusTotal

VirusTotal is an Alphabet (Google) owned company and works with more than 60 security vendors to aggregate malware, virus and other security data. It provides both file scan (malware) and URL scan services free of charge to researchers and the public. After a URL is submitted directly to VirusTotal, it queries the database of those partners and the results are stored in VirusTotal’s database for future reference. They also provide an API that allows researchers to query the VirusTotal database to check if an URL has already been labeled malicious. This is what was used to inform this research.

Because we were querying VirusTotal's database rather than that of providers, we gave domains a ‘bedding in period’ before scanning in order to allow sufficient time for domains to become weaponized and for this data to be passed to VirusTotal. This was typically 7 days although many domains were rescanned after 14 days.

It is worth noting that security vendors often have different results. A URL might be labeled benign by Sophos but labeled malicious by Fortinet. Due to the nature of the research, we decided to set the threshold as low as possible, meaning that if any vendor returned a "malicious” label, the domain was regarded as malicious for the purposes of the study.

Threat detection count

Tracking themes

In phase 1, we looked exclusively at Covid-related token domains using strings, such as ‘covid’ and ‘corona’. However, it quickly became apparent as the pandemic evolved, that new attack vectors would emerge based on evolving public concerns, media coverage, moral panics and government actions.

Using natural language segmentation techniques (explained below) we analyzed our corpus of existing data to identify new niches used by bad actors to exploit the pandemic. These were then added to our daily monitoring.

At the time of publication, we are monitoring the following keywords:

- Corona

- Virus

- Covid

- N95

- Pandemic

- Cure

- Vaccine

- Mask

- Sanitize/sanitise

- Disinfect

- Anti+body/bodies

- Remote

- Lockdown

- Isolation

- Stimulus

- Unemployment

- Contact+tracing

- Social+distancing

For those domains labelled as malicious, we then used WHOISXML API to pull complete WHOIS data in order to further inform the analysis.

Domains over time

It is perhaps not surprising that malicious activity has tracked closely with the spread of the disease. As the world woke up to the fact that the virus would not be confined to China and neighboring states, global media coverage found itself consumed with the story; government strategies were changing by the hour and social media propagated misinformation at a rate never seen before.

After the first few weeks of data collection, it became apparent that we were able to track malicious activity to specific events. For example, when the World Health Organization (WHO) designated an official name to the disease caused by Coronavirus (COVID-19), there was a significant spike in malicious activity as bad actors moved on the Covid opportunity.

When the Dow Jones suffered its biggest single-day slump on record and Chinese manufacturing ground to a halt, there was another clear spike; and when the outbreak was officially confirmed a ‘pandemic’, the increase in malicious activity became exponential, much like the spread of the disease itself.

Analyzing broad themes throughout the pandemic

While token domains have been, by-far-and-away, the most utilized domain type so far, we wanted to understand the wider themes that bad actors were using to entice users into clicking.

To achieve this, we used natural language word segmentation techniques based on the Google Web Trillion Word Corpus, to pull bigram and unigram data from our existing database of domains. We then filtered out token terms to better identify common subthemes.

We then used this data to expand our search radius for additional malicious domains.

Almost immediately, we can see a few common themes emerging from the data, the most obvious of which is masks. A global shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) left healthcare organisations and members of the public desperately seeking medical-grade masks. On top of this, there was a lot of mixed messaging from both governments and NGOs as to the usefulness of masks. This state of confusion combined with a genuine need to PPE manifested in the form thousands of mask-related domains being created in a short space of time.

Similarly, when Zoom found itself the de-facto video conferencing platform for those in lockdown, malicious domains began popping up to take advantage of this new hot-ticket technology. As stories began to break raising privacy concerns about the company, malicious activity again spiked.

Hiding in the plain sight: Obscurity in the cloud

Throughout our analysis we noticed thousands of domains resolved to single IPs. This often occurs in shared hosting environments or when the domains use Content Delivery Networks (CDNs). By far the most abused IP in our dataset was 184.168.131[.]241 belonging to hosting giant GoDaddy in Scottsdale, Arizona. This IP was associated with 3,285 domains gathered throughout our process. Given that GoDaddy is the largest hosting provider in the world, hosting more than 15% of all websites, it’s not surprising that the majority of activity has transpired on their infrastructure, most of which is provided by Amazon Web Services.

Registrars have been taking decisive action to combat the huge amounts of malicious activity. GoDaddy said in a canned statement:

"To date, our teams have already investigated and removed COVID-19 fraud sites in response to reports, and our vigilance will continue long after the COVID-19 crisis comes to an end [...] We’ve equipped our teams with the tools and technologies they need to promptly investigate any and all reports of abuse."

However, as we explain below, the threats are becoming much more nuanced and therefore the battle to suppress this activity is going to become more challenging as we move into the later stages of the pandemic.

It's also worth noting that there are many instances when a single domain name resolves to multiple IPs. This is either because a domain name has multiple redundant hosts or, again, is using a CDN, such as Cloudflare. In such cases, thousands of domains may resolve to the same IP of an edge server based on the user's physical location. This geographical redistribution of resources reduces network latency and improves service availability; however, because malicious domains share the same IPs as many other benign domains, it also provides a layer of anonymity for bad actors.

While many-to-many IP mapping won’t mean a great deal to members of the public, it can prove a challenge for IT departments trying to block malicious domain names by IP. Using GoDaddy’s IP address above as an example, blacklisting 184.168.131[.]241 would render some 8,665,477 domains unreachable.

Where are malicious domains being hosted

The anatomy of attacks: Fighting an infodemic

Over the past 5 months, it has become clear that we are not just fighting a pandemic; we are fighting an infodemic. The WHO describes an infodemic an over-abundance of information - some accurate and some not - that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it. It is in this paradoxical environment, where information is both abundant and absent in equal measure, that cyber-criminals have been able to thrive.

While some of the sites included in our dataset were part of sophisticated malware attacks, the vast majority were found to be associated with low-level phishing campaigns. We call these ‘low-level’ because there is nothing novel or unique about the methods being used, but the terminology should not detract from the fact that phishing remains the most widely used and devastating malicious technique in existence.

The reason for this is two-fold - first and foremost, because phishing always has been (and probably always will be) incredibly effective. It targets the weakest link in the cybersecurity chain - human error; and it relies on a massively scalable fire and forget approach.

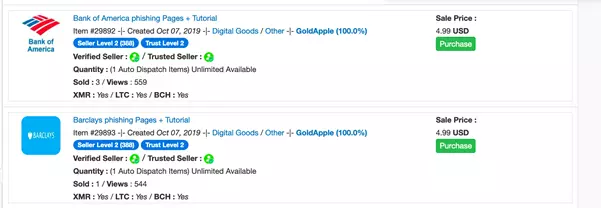

The second reason is that the barrier to entry for carrying sophisticated large scale campaigns has been all but removed. Actors can buy ‘phishing kits’ off-the-shelf on the dark web and execute them with almost zero technical knowledge.

These kits provide everything needed to launch a sophisticated attack including highly polished landing pages, as well as the various php files needed to capture data and obfuscate malicious domains from vendors and authorities. After just three minutes of searching well-known .onion marketplaces, we were able to find kits for Bank of America and Barclays.

During our research we found that many of these kits included various obfuscation techniques and guides on how to avoid detection. In a recent study, researchers recreated three of these obfuscation techniques: (1) Redirection, using a URL shortener service to obfuscate the phishing URL. (2) Image-based obfuscation: using a screenshot of the website that was being mimicked (PayPal) as the background image of the phishing site overlaying login forms on top of the image. (3) PHP obfuscation, using common techniques to mask the intent of the code. They submitted each of the sites to VirusTotal and then resubmitted after a week.

While redirection did not have much of an impact, image and code-based obfuscations proved highly effective with the average number of malicious labels dropping from 12.1 to 4.5 and 2 respectively.

This suggests that many vendors are unable to handle simple obfuscation schemes and so the true number of malicious phishing campaigns could be as much as 500% greater than our research indicates.

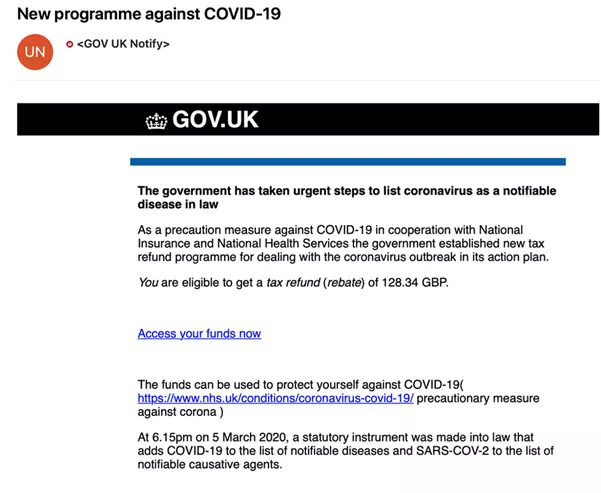

In terms of the pandemic, the most sophisticated campaigns we have seen are those that impersonate official sources of information such as the World Health Organization or government bodies. As previously mentioned, the fact that citizens are desperately searching for a signal in the noise has created ideal conditions for phishing campaigns to thrive. Below is an example of an attack purporting to be from the UK government.

As can be seen, these are much more polished than the average spam email; well written with correct logos and official sites included to gain the victim’s confidence.

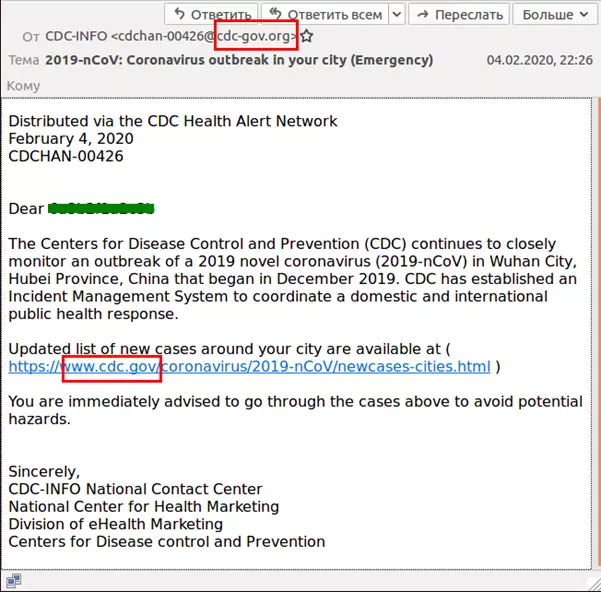

Below is an email claiming to be from the Center of Disease Control (CDC):

The masked link leads through to a page that emulates a Microsoft Outlook interface promoting the user to sign in. Both the email and the landing page are highly convincing and are likely to lead to successful capture of user data.

Moving underground: We've passed the peak, but threats are becoming more focused

Thankfully, the overall spike in COVID-related domain registrations is declining; however, we are still seeing anywhere between 700 to 1,200 COVID-related domains registered each day.

Sophos, a member of the CTC, has reported that it is seeing up to 80,000 hits per day on COVID-related domains among Sophos customers, however this represents a decline from a weekly peak of 110,000 visits per day, and the peak rate of 130,000 visits per day on April 14.

While the broad stroke Corona/Covid themed domains are waning, the reality is that malicious actors have not given up, but are now focusing their efforts in more targeted ways. This is concerning for a number of reasons. First, there is less chance that these campaigns will be identified by registrars and the threat intelligence community as their connection to the pandemic is becoming more abstract.

Second, while the overall number of malicious domains is decreasing, their potency and efficacy is increasing. Malicious campaigns are now addressing our most intimate concerns. When will my children return to school? Will I lose my job? Is there anything more I can do to keep my loved ones safe? It is these - truly human - questions that will fuel the 'second peak' of malicious activity. This is the next battlefront in the digital pandemic.

Explore the data

Direct data downloads:

| ProPrivacy | VirusTotal malicious domains | Download .csv |

| WHOIS data for malicious domains | Download .csv |

| Complete dataset | Download .xlsb |

Advice for citizens

Always treat emails and text message that require immediate action with suspicion. Phishing campaigns use ‘lures’ that target human emotions or requirements. Treat any communications related to COVID-19 with caution. For example - COVID test results and PPE availability.

Always double check links before clicking. Hover over a link and look in the corner of your browser. If in doubt, copy the link without opening and paste into: https://www.virustotal.com/gui/home/url

Do not trust URLs that have been shortened!

Don't trust sites just because they have the 'safe' padlock symbol or use SSL (https).

If you are unsure of whether or not to trust a source, contact the sender using a different channel of communication such as phone.

If you are using a cloud mail service provider (GMail, Outlook, Yahoo, Apple etc.) and you receive phishing emails, report these to your provider. There is usually a button within the interface to report such emails. If you get a suspicious email to your business address, forward the message to your IT department.

You are encouraged to report any suspicious activities it to authorities.

US Residents

The FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3),

Email FTC Consumer Information

UK Residents

National Fraud Intelligence Bureau

EU Residents

EUROPOL

Text message (SMS) spam

US Residents

Forward it to 7726 (SPAM).

UK Residents

Information Commissioner's Office