“There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time, but at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to."

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

The Panopticon (literally “all observed”) is the invention of renowned English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham. It is a prison building designed to allow a single watchman to observe all the inmates.

Of course, such a watchman cannot keep an eye on all the inmates all the time, but the fiendish genius of this design is that the inmates know they can be watched at any time. Knowing this, the inmates would be forced to behave at all times as if they were being watched if they wished to avoid disciplinary measures. Bentham hailed the Panopticon as,

"A new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example."

The Panopticon has since become a powerful metaphor for the “chilling effect” that surveillance has on free speech. As George Orwell well understood, when people fear that anything they do might be watched at any time, they will behave accordingly,

“You have to live - did live, from habit that became instinct - in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.”

The mass surveillance performed by governments on both their own citizens (and just about everybody else), as revealed by Edward Snowden, is often compared to the Panopticon. Your government can and does spy on just about everything that you do online.

Any rational person probably realises that most of what we do online will be lost in the oceans of data that spying agencies must process, but are also aware that the full gaze of such agencies could be turned on us at any time, and without our knowing it. As the old maxim goes, “it's only paranoia if they aren’t out to get you!”

There already exists plenty of evidence to show that when people believe they are subject to mass surveillance they behave accordingly, self-censoring what they say to others, and what they look at on the internet. Most such evidence, however, can be (and has been) dismissed by the US government and its ilk as purely anecdotal. A new study, however, provides empirical evidence that Snowden’s surveillance disclosures have had a “scary effect on free speech.” As the Washington post notes,

“If we think that authorities are watching our online actions, we might stop visiting certain websites or not say certain things just to avoid seeming suspicious.”

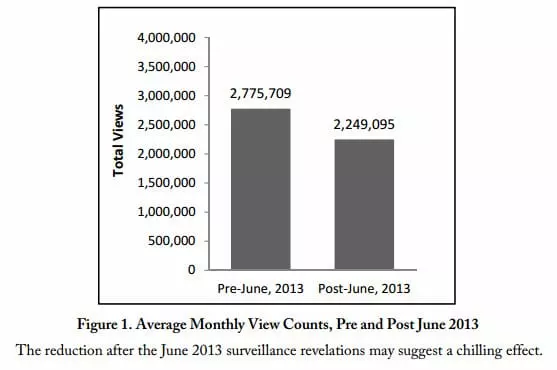

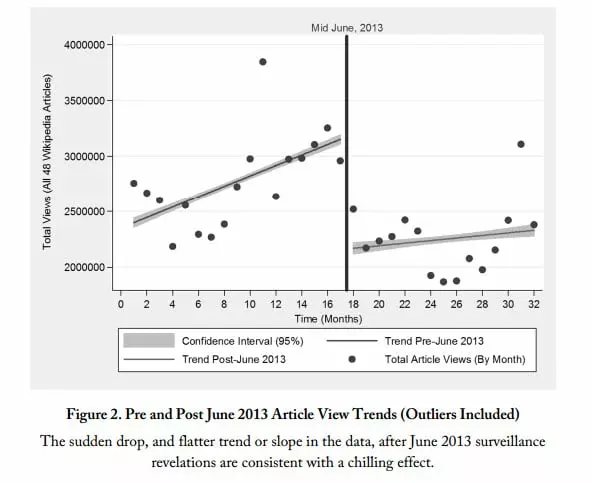

The study was performed by Jonathon Penney, a PhD candidate at Oxford. In it, he analyses Wikipedia traffic over a 32 month period before and after Snowden’s NSA revelations in June 2013 (of which 87 percent of Americans were aware), using a keyword list taken from the Department of Defense’s own list of “terrorist related” terms.

“Wikipedia is both a massively popular medium, but one that is also growing in content and scope. As such, any observed chilling effect would implicate a large number of Internet users (accessing Wikipedia) doing something wholly legal—accessing information and knowledge in an encyclopedia—and, arguably, such chilled or reduced use would run counter to these Wikipedia use and content trends.”

What Penny found was that Wikipedia searches for terms such as “al-Qaeda,” “car bomb” or “Taliban,” declined 20 percent in the months following Snowden’s revelations. As Penney notes,

“You want to have informed citizens. If people are spooked or deterred from learning about important policy matters like terrorism and national security, this is a real threat to proper democratic debate.”

Penney also comments on how long this cooling effect lasted,

“I expected to find an immediate drop-off in June, and then people would slowly realize that nobody is going to jail for viewing Wikipedia articles, and the traffic would go back up. I was surprised to see what looks to be a longer-term impact from the revelations.”

The report provides objective empirical evidence that backs up studies such as that by PEN America, which found that:

- 1 in 6 writers avoided writing or speaking on a topic they thought would subject them to surveillance

- Another 1 in 6 seriously considered doing so

- 28% (nearly a third) curtailed or avoided social media activities, and another 12% have seriously considered doing so

- 24% deliberately avoided certain topics in phone or email conversations, and another 9% have seriously considered it

- 16% avoided writing or speaking about a particular topic, and another 11% have seriously considered it

- 16% refrained from conducting Internet searches or visiting websites on topics that may be considered controversial or suspicious and another 12% have seriously considered it;

- 3% declined opportunities to meet (in person, or electronically) people who might be deemed security threats by the government, and another 4% have seriously considered it

So much for America being “the land of the free.” As Glen Greenwald summarizes in his discussion on the new report,

“There is a reason governments, corporations, and multiple other entities of authority crave surveillance. It’s precisely because the possibility of being monitored radically changes individual and collective behavior. Specifically, that possibility breeds fear and fosters collective conformity. That’s always been intuitively clear. Now, there is mounting empirical evidence proving it.”