The internet-using public is increasingly aware of the dangers to privacy posed by HTTP browser cookies - small text files stored on your computer by websites which can be used not only to identify you when visiting a particular website, but also by other websites so that you can be tracked as you surf online.

In May this year (2013) the EU ‘cookie law’ came into force, requiring EU websites and all websites that serve an EU audience to ask permission from visitors before leaving ‘non-essential’ cookies on their computers. In practice, implementation and enforcement of the law has been patchy and only partially effective at best (and not helped by some very vague wording), but it has helped to raise awareness about cookies among netizens everywhere.

Websites (and in particular third party analytics and advertising domains) however gain a great deal financially from the use of cookies and have thus looked for new ways to uniquely identify and track website visitors by other means. One of these methods is the use of supercookies (including Flash cookies and zombie cookies), and another is browser fingerprinting (HTTP E-Tags, web storage, and history stealing are also lesser used methods which we will discuss in another article).

What is browser fingerprinting?

Whenever you visit a website, your browser sends data to the server hosting that site. This data includes basic information, including the browser name, operating system, and exact version number of the browser. This information is known as passive browser fingerprint because it happens automatically.

However websites can also easily install scripts that ask for additional information, such as a list of all installed fonts and plugins, supported data types (so-called MIME types), screen resolution, system colors and more. Because this information has to be solicited from your browser, it is known as active fingerprinting.

Taken altogether, the various fingerprint attributes can be almost instantly (it takes just a few milliseconds to run algorithms that compare millions of fingerprints) combined to create a unique fingerprint that can be used to very accurately identify an individual user, no matter if cookies have been deleted or IP address changed between website visits.

How unique is your browser fingerprint?

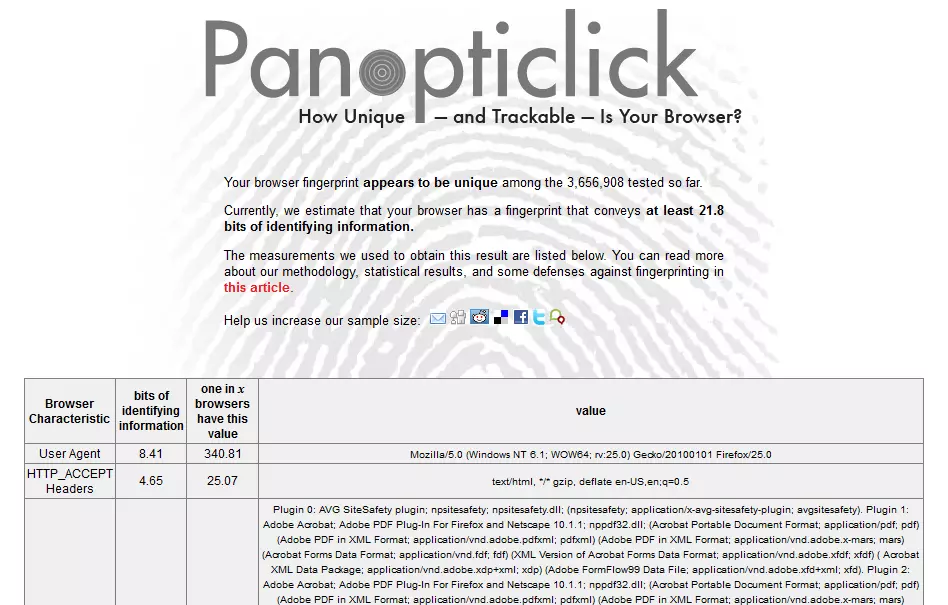

The EFF’s research shows that ‘if we pick a browser at random, at best we expect that only one in 286,777 other browsers will share its fingerprint.’ As part of its investigation it has created the Panoptoclick website, which actively fingerprints your browser, and tells you how unique it is.

We use a lot of privacy-related plugins in our browser, which ironically makes us more unique, and therefore identifiable by fingerprinting.

Can I change my fingerprint?

Every time you install a new font or plugin, or otherwise change one of the fingerprinted attributes, you change your fingerprint. The most important attributes in this regard are the list of installed plugins, supported MIME types, and installed fonts, which alone when combined with the browser’s User Agent (which provides information about the browser) allow unique identification with an 87 percent accuracy.

Unfortunately, the EEF determined that even when ‘fingerprints changed quite rapidly. Even a simple heuristic was usually able to guess when a fingerprint was an "upgraded" version of a previously observed browser's fingerprint, with 99.1% of guesses correct and a false positive rate of only 0.86%’

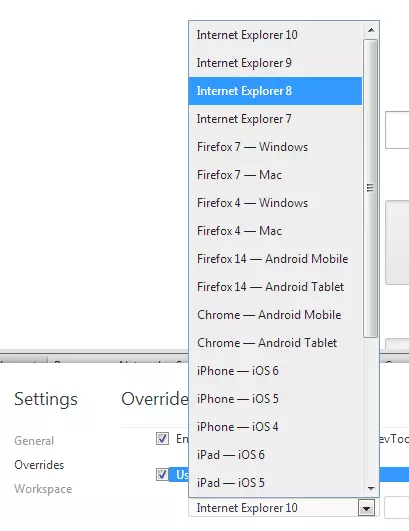

It is possible to change a browser’s User Agent, which has the most dramatic effect on changing your fingerprint, but many websites rely on being given correct User Agent to function properly, so this is not an ideal solution. In addition to this, by changing your User Agent you actually increase your browser’s uniqueness (we discuss this more below), but if you do want to try doing it, then check out guides for doing so in desktop browsers, Android and iOS Safari.

Changing our User Agent in Chrome

One of the most frustrating and paradoxical aspects of fingerprinting is that any measures you take to prevent tracking, such as blocking Flash cookies or changing your User Agent, actually make you more uniquely identifiable. The truth is that protecting yourself from being fingerprinted is currently difficult to the point of being impossible, but there are things that you can do to minimize the problem.

The most important of these is to use a popular browser that is as ‘plain vanilla’ (i.e. as unmodified) as possible, so that you blend in with the majority non-tech savvy internet users who never install additional plugins or otherwise tamper with their software. Firefox and Chrome are therefore good choices for desktop users (Safari isn’t too bad, but Microsoft Internet Explorer gives away more identifying information than the others do), while iOS Safari users are safer than Android users because iOS Safari is less customizable (and therefore less unique) than the stock Android browser. Ideally, you should also use the plainest Operating System possible, so a freshly installed Windows 7 (the world’s most popular OS) with no additional software or fonts would be best, although admittedly totally impractical for most people.

While most privacy-enhancing measures (which we cover in some detail in our Ultimate Privacy Guide) actually decrease your privacy when it comes to fingerprinting, the EFF noted that Torbutton (and the Tor network in general) gave ‘considerable thought to fingerprint resistance’, and that ‘NoScript is a useful privacy-enhancing technology that seems to reduce fingerprintability.’ Commendable as these efforts are however, such measures are not perfect, as fingerprinting expert Henning Tillmann explained, ’Everyone using Tor has a similar browser fingerprint and if a website only has one visitor using Tor this makes him or her unique and identifiable.’

Tips to prevent tracking

- Use a freshly installed copy of Windows 7

- Use an unmodified Chrome or Firefox browser

- Use a VPN service to mask your IP address and encrypt your browsing data (or use Tor)

- Clear browser cache and cookies after every session (working in the browsers ‘privacy mode’ should have a similar effect)

- Disable or don’t install JavaScript (unfortunately, though, many websites will not work properly without it)

- Disable or (better yet) don’t install Flash. Unfortunately however again, Flash is responsible for a lot of the more user-friendly features and functionality found on the web.

- Visit the EFF’s Panoptoclick website to see how effective your measures have been

Conclusion

Browser fingerprinting is a powerful technique, and fingerprints must be considered alongside cookies, IP addresses and supercookies when we discuss web privacy and user trackability. Although fingerprints turn out not to be particularly stable, browsers reveal so much version and configuration information that they remain overwhelmingly trackable.

As internet users have become more aware of privacy and tracking issues, so have those who would track us become increasingly devious in their methods of doing so. With fingerprinting this has reached the point that it is almost impossible to prevent (although as noted above there are steps that can be taken to make it more difficult). The EFF, therefore, concludes its report by saying that the answer lies in government action and legislation, and that ‘policymakers should start treating fingerprintable records as potentially personally identifiable, and set limits on the durations for which they can be associated with identities and sensitive logs like clickstreams and search terms’.

Now it has to said that we have very limited faith governments’ will or ability to enact such changes (although the EEC ‘cookie laws’ at least show some positive intention in this direction), so in the meantime, we will just have to take as many measures as we can live with (since all measures impact our user experience in some way), and hope for the best.